What is a Surf Park? There are various types of surf parks. The most common are outdoor surf pools. Dynamic wave pools are large, typically over 10 times the size of an Olympic pool, allowing for a few seconds of surfing over 100 meters or more. Static wave pools are smaller. Surfing infrastructures can also be created by installing motors in existing water bodies or by promoting the formation of surfable waves in rivers or along the coast. The first dynamic wave pool designed exclusively for surfing opened in Wales (Adventure Park Snowdonia) in 2015 and closed in 2023, illustrating the rapid obsolescence of these infrastructures due to intense competition among industry players.

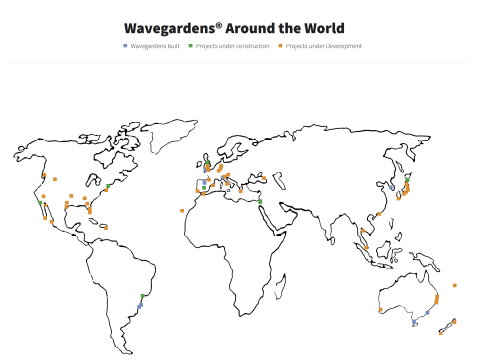

Development of Surf Parks Worldwide Currently, there are about 25 dynamic wave pools globally, but more than 200 surf parks are in development. This demand is driven by the popularity of surfing, the fastest-growing water sport worldwide, which has gained visibility through its recent inclusion in the Olympic Games. According to industry leaders, the future looks bright. They anticipate exponential growth in the coming years, with the number of surf park openings doubling year over year for several years (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Wavegarden Technology Surf Parks (the market leader) worldwide. There were eight operational Wavegarden surf parks in June 2024.

The main argument of the surf park industry is to make surfing accessible to everyone, including in landlocked areas. Before the advent of surf parks, surfing could “only” be practiced in certain coastal spots at specific times of the year, with increasing issues of overcrowding. Promoters also highlight the greater safety of surf parks, with waves calibrated at will and the absence of sharks, dangerous currents, and competition among surfers for waves.

This trend towards seeking spectacular yet less risky experiences at the cost of reduced authenticity is characteristic of modern day tourism. Promotions for surf parks frequently emphasize their record dimensions, such as in South Korea, Florida, or Abu Dhabi. This extravagance comes at a high environmental and social cost. One consequence is the commodification of an activity (surf) that was previously free, the tendency for individuals to no longer distinguish between real and fake, and a form of secession from the rest of society, as these tourist bubbles often become social bubbles as well.

The Structuring of the Surf Park Industry In 2012, a company was created to accelerate the development of surf parks: Surf Park Central. It was founded by John Luff, an industrialist, and Dr. Jess Ponting, a professor of “sustainable surf tourism” at San Diego State University. In September 2013, this company organized the first world summit of surf parks in California, and the event has been held annually ever since. The goal is to support the growth and evolution of surfing “beyond the ocean,” bringing together developers, investors, operators, and industry professionals to promote the sustainable growth and development of surf parks worldwide. Much of the information presented here comes from this company, which, although based in the United States, covers the global development of surf parks.

Who Benefits from Surf Parks? The willingness to pay by surfers visiting a surf park is of great interest to surf park industrialists. The latest “Consumer trends report” released by Surf Park Central in January 2023 surveyed a panel of 1028 surfers. The survey was distributed online in 2022 in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. The study participants were mainly men (90%), affluent (average salary between $100,000 and $150,000 per year), and highly experienced in surfing (11 to 15 years on average). The study lacks guarantees of representativeness and quality, but it is the only one available on this topic. It shows that 99% of surfers who responded to this survey are willing to surf in a surf park, with 33% having already done so. This unrealistic figure indicates that the survey is likely biased and that only surfers favourable to surf parks participated. It also shows that an “average” surfer is willing to pay $84 (€78) for ten “perfect” waves, a value that has increased significantly since 2015. Industrialists, therefore, have little incentive to offer a lower price. Another study focused on 534 surfers who visited a surf park (URBNB Surf in Australia, The Wave in England, Waco and Surf Ranch in the USA). They were asked how much they spent in total during their visit, on average: $290 (€270), with differences between surf parks. Even in the least expensive surf park, half of the visitors spent over $100. These high prices are logical because these infrastructures are costly to build and operate; promotional messages highlighting the family-friendly and inclusive nature of surf parks must therefore be strongly relativized.

The luxurious nature of these surf parks is also evident in the recent trend of including them in high-end real estate projects. Due to their novelty and spectacular nature, surf parks are now more attractive than golf courses for real estate investments. An evolution in the field of hyper-luxury involves constructing residential complexes that include surf parks exclusively for the use of property owners or tenants of neighbouring residences. The presence of a surf park (along with a golf course) in these private gated communities becomes a selling point. Such gated communities built around a surf pool already exist in Brazil and are planned in Australia, Canada, and the USA.

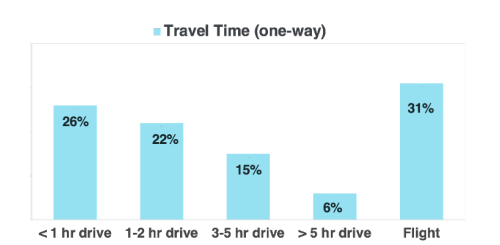

Finally, the Surf Park Central study showed that surfers often travel several hours to visit a surf park, with 31% traveling by plane, resulting in a high carbon footprint (Figure 2). Thus, these surf parks attract a distant public and not only a local one. In fact, “road trips” including visits to several surf parks are beginning to emerge. Therefore, it seems unlikely that the presence of surf parks will encourage surfers to travel less and reduce their carbon footprint, quite the opposite.

Figure 2: Distance travelled by surf park visitors

Acceptance of Surf Parks The growth of the surf park sector has become an argument for its promoters: since there are more and more surf parks across the world, why not build one here? It is in countries already equipped with surf parks, such as the United States or the United Kingdom, where most projects emerge. The surf park industry acknowledges public acceptance issues for these infrastructures but they argue that this resistance is due to misunderstandings. They cite the example of a report by famous comedian and social commentator, John Oliver, who called the project to build four surf parks in the Californian desert “monumentally stupid” given the water waste it would entail. They highlight the numerous health benefits of surfing and the interest of surf parks for local economies. Regarding water use, they defend themselves by comparing surf parks’ water consumption to that of golf courses.

However, this comparison is neither valid nor relevant. The water consumption of existing surf parks is kept secret, and comparisons with water use in golfs are based solely on estimates for planned surf parks, which the industry has every incentive to minimize. Additionally, the water used to fill wave pools must be potable, unlike the water used to irrigate golf courses. Moreover, in a surf park, water eventually evaporates, whereas in a golf course, it partially returns to groundwater. In reality, golf projects are increasingly contested. And most importantly, relativizing the environmental impacts of an activity (here, wave pools) by diverting attention to another more water-intensive activity (e.g., golf) is a typical tactic of climate inaction.

An Eco-Responsible Industry? According to its champions, the surf park industry can and must “go green”. Their idea is to eco-certify surf parks. To date, however, the only company practicing this eco-certification (Stoke) comes from the industry itself, as one of the co-founders is Jess Ponting, the current CEO of Surf Park Central. Thus, it is both judge and party! This certification does not provide for the publication of annual water and energy consumption, a central aspect of the sustainability debate for these surf parks. So far, industrialists have always refused to be transparent on these points, so claims for eco-responsibility are not serious.

Such “friendly” eco-certification is of interest to the surf park industry: a survey by Surf Park Central shows that 91% of surfers are willing to pay more for an eco-responsible surf park and 68% would like to find information about environmental issues affecting natural ocean surf spots in surf parks. Human science studies have shown that exposure to nature during a recreational activity, such as surfing, indeed engenders a pro-environmental attitude. The problem is that such an attitude does not necessarily lead to environmentally consistent behaviours: surfers have a much higher ecological footprint than football players, for instance. This is called cultural dissonance.

Among the measures considered by the industry to green surf parks and thus reassure their users are using renewable energy instead of fossil energy and ecological compensation (for wasted water and biodiversity loss). However, these efforts result either in a lesser evil (the cleanest energy being the one we do not consume) or outright trickery, depending on the implementation details. For example, some surf parks highlight a net energy consumption equal to or less than zero thanks to solar energy, without specifying that they are not self-sufficient in winter. A summer production surplus does not offset a winter deficit, which puts additional pressure on the public power grid.

Conclusion The surf park industry envisions extremely rapid development and shows great opacity in its use of natural resources. Ecocertification procedures are only voluntary and hardly compensate for the environmental impacts. According to the environmental organization Surfrider Foundation Europe, environmental concerns of wave pools outweigh their value: “the reality of climate change should force us to rethink our growth models to reduce natural resource consumption and reconcile our relationship with nature.”